I believe that science faculty members at large public universities have a special role to play to educate students about basic science literacy. The two 3-credit mathematics and natural science course requirements for general education are our opportunities to do this.

I led a pedagogic method research project to address the challenge of teaching non-science major students the concept of deep geological time. We published the article “Looking Back to Move Ahead: How Students Learn Geologic Time by Predicting Future Environmental Impacts results” in the peer-reviewed educational publication Journal of College Science Teaching (Zhu et al., 2012). Through the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning program, my collaborators and I gave a campus-wide seminar series, and also conducted a workshop on “Decoding the Disciplines: Helping Students Through the Bottlenecks,” hosted by Kent State University with the participation of faculty from multiple institutions.

More recently, I have turned my attention to teaching students about climate change, which appears to be an even more stubborn learning bottleneck than deep geological time. The subject of climate change presents a well-known conceptual challenge. Many articles and interviews by Nobel laureates in behavioral finance, including Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler, and other scholars, show that climate change is an exceptionally amorphous intellectual concept, as there is no deadline, no geographic location, no single cause or solution, and no obvious enemy. Although there are well-known examples of climate change impacts that include the melting of Greenland and Antarctic glaciers, coastal sea-level rise, and polar bears on break-away ice floes, the US society’s wide skepticism and indifference toward climate change, makes communicating or teaching with these and other analog examples very challenging.

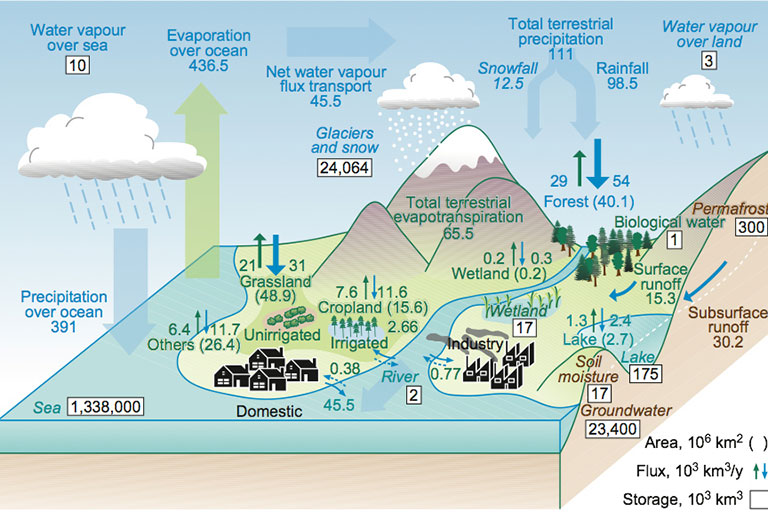

In the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced instruction at nearly all educational institutions online. Due to a lack of resources, online instruction poses special challenges, particularly for K-12 schools. This situation motivated the bright and idealistic students in my "H241 Sustainability: Water Resources" class to develop two online active learning lessons for distribution. Each lesson uses the FutureWater platform (https://futurewater.indiana.edu), which hosts hydrological models of the Wabash River basin that covers most of Indiana, as an online teaching tool. K-12 and lower-level university students can use the information on this platform to analyze Indiana watersheds and environmental changes associated with our water. The lessons also include:

- A politically neutral and accessible approach to teaching climate change.

- An emphasis on science practices including developing and using models, analyzing and interpreting data, and engaging in argument from evidence.

These lessons were distributed to Indiana science teachers through the Integrated Program in the Environment in August 2020.